Hello Readers —

Election day has come and gone. With newfound time, I hope to write here more often. For those who are new, this is Bipolar & Bipartisan — a newsletter focused on mental health public policy and centering those with lived experience in the conversation about mental healthcare.

Today, I’m opining about the intersection of mental health and democracy. Specifically, I’m writing about why improving civic infrastructure can simultaneously strengthen our minds and our republic.

Whether you are thrilled or exasperated about last week’s election results, I hope you will consider the role all citizens play in our democracy.

Thanks for reading,

Tyler

TL;DR

The basic arguments I make below are these:

Our democracy is backsliding, and voters are noticing;

Mental health outcomes are getting worse;

Both can be attributed to a retreat from communal activities and spaces;

Increasing civic engagement can strengthen democratic institutions and senses of belonging;

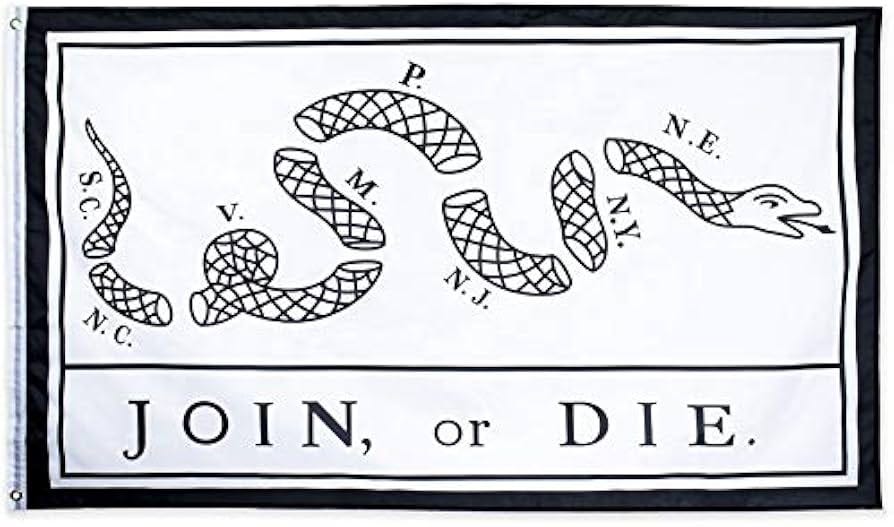

We must “Join or Die” — as Americans for our democracy, and as humans for our mental health

The Problems

The United States is in a period of democratic backsliding. Meanwhile, Americans are facing more mental health challenges than ever. The two are connected.

First, consider where our democracy is. The Freedom House is a global nonprofit that advances freedom, liberty, and self-governance around the world. Each year, they evaluate each country on 25 factors including freedom of expression, individual rights, the rule of law, political participation, government functionality, and political participation. For thirteen straight years, U.S. democracy has been in decline. There are many reasons why, but today we are behind countries including Panama, Argentina, Greece, and Belize. We are also behind European peers including the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Italy, Sweden, Finland, and more.

Americans are concerned about their democracy, too. Public trust in government to do the right thing has collapsed from 77% in 1964 to 22% today. As a result, voters are beginning to prioritize candidates who prioritize democracy in their platforms. According to NBC exit polling this week, 34% of voters said democracy was the issue that most influenced their vote, ahead of the economy (31%), abortion (14%), and immigration (11%). Yet, we are divided on what democratic threats we face. Republicans are more concerned with freedom of speech, election security, and non-citizen voting, while Democrats are more concerned about voting access, the Electoral College, and the rise of authoritarianism.

There are countless ways to quantify what has gone wrong in the United States. Consider:

The share of voters who say they have confidence in election results has declined by 25% since 2004.

Growing shares of both parties believe members of the other party are immoral, dishonest, and lazy.

In just fifteen months the number of Americans who said bipartisan compromise on major issues like the environment, the budget deficit, and immigration declined by a third.

The number of competitive U.S. House races has been cut in half over the last two decades.

That has left us in a situation whereby most elections are decided in partisan primaries, in which fewer and more ideologically extreme voters vote: in 2024, 87% of U.S. Representatives were effectively elected by 7% of the voting age population.

Second, consider the state of our mental health. Despite voluminous amounts of new research to help us understand the topic and less stigmatization of the topic so we can talk about it more, we are worse off than ever before. Since 2000, age-adjusted suicide rates in the U.S. have risen by 35%, reaching approximately 14.0 per 100,000 people in 2021, with a temporary decline in 2019 and 2020. In 2023, 40% of American students reported persistent sadness. American adults are increasingly lonely, with 10% saying they feel lonely every day — and those aged 18-24 are doing the worst.

Suicide, depression, loneliness rates are all trailing indicators. Leading indicators tell us why this is happening. Consider:

The number of teens who “meet up daily” with friends has been cut in half since 1991. Perhaps driven largely by the fact that the average teen spends 7 hours and 22 minutes per day on screens; 43% of their teen waking hours. That’s crazy!

Usage rates of methamphetamine, cocaine, opioids, and especially fentanyl are rising fast.

Despite increased demand, the number of beds available at in-patient mental health facilities is declining.

In Colorado, where I have twice been hospitalized, there are just 10.8 beds per 100,000 people — startlingly below the national average of 83.

10% of Americans with a mental illness do not have health insurance; meanwhile, another 10% have private insurance that does not cover mental healthcare.

In short, it is bad out there, for both our democracy and our minds.

A Driver of Mutual Dysfunction

The central part of my argument in this missive is that declining civic engagement is bad for both mental health and our democracy, and that by increasing our rates of belonging we can cure both our minds and our republic.

Why? When people belong to institutions, spend time with neighbors, do things with friends, visit with family, and engage in collective action they feel more connected to other human beings. When they are more connected to other human beings more often they become less lonely, anxious, and disconnected. At the same time, they are more likely connecting with people they are different from, strengthening their communities, and solving both mundane and complicated problems.

The data is clear that Americans are retreating civically. They have been slowly retreating from community spaces to their homes for several decades; at the same time, the indicators listed above suggest our capacity to govern our minds and our republic diminished. Americans' declining civic engagement is not just correlated with poor mental health and democratic backsliding, but rather a cause of both.

Data on Disengaging

The idea that America’s social capital has been a key driver of democratic retreat is perhaps most attributable to Robert Putnam. Putnam began raising alarm bells around the turn of the millenium, including via his 544-page tome Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Putnam’s evidence that Americans’ disengagement from their communities had slowly been declining was overwhelming. Putnam blamed the arrival of televisions, post-war generations, increased work pressures on our time, political polarization, and the decrease in the number of civic organizations.

Unfortunately, the leading indicators of social capital continue to decline.

In 2022, charitable giving was lower than any time since 1995; volunteerism has been cut by a fifth since 2005; and attendance at local government meetings is down.

Those who do show up to community meetings are whiter, wealthier, richer, and more likely to be homeowners — tilting public policy outcomes in their favor.

Belonging to unions has been cut in half since 1983, to religious groups by a third since 2000, and to fraternal organizations like the Freemasons, the Odd Fellows, and Elk Club are in rapid decline.

The U.S. Census Bureau’s American Time Use Survey goes back decades and tells us how much less time we spend with each other.

Chart from Jonathan Haidt’s Anxious Generation, which I’m reading now.

Why Social Capital is Important

Social capital can be broadly defined as “the networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society, enabling that society to function effectively.”

Social capital and belonging is important for our mental health for perhaps obvious reasons. Engaging with friends and family makes it less likely we will feel lonely. Doing physical activities with others in a running club, in an adult intramural league, or coaching a team is good for the body and in turn the mind. Solving problems with a community group can give people a sense of purpose. Volunteering and donating makes people feel better. Spending time in community spaces connects individuals to people of different racial, economic, and geographic backgrounds

Social capital is important for our democracy for perhaps less obvious reasons. Government is being asked to solve too many problems, and groups of citizens are often more equipped to diagnose them and find solutions. We can curb rising polarization and out-group hatred by spending time with people different from us. We are more likely to hold ourselves and our elected officials accountable for bad behavior when we trust each other. Engaging in public debates and forums increases access to information, improving transparency that can root out corruption.

What Democracy Really Is

People often conflate democracy with elections. They also conflate democracy with politics.

Democracy, though, is more philosophical and less mechanical. It is ultimately about the ways in which people hold and exercise power in order to govern themselves, solve problems, and ensure justice. Democracy does not just happen through elections like Americans participated in on Tuesday. Rather, it happens every day and any time citizens come together to reconcile differences, engage in collective action, and hold each other accountable.

When the Frenchman Alex de Tocqueville was writing about American democracy in the early 1800s he was not primarily writing about our Constitution, how we vote, or how a bill becomes a law. Rather, he was writing about Americans’ unusually high rates of participation in society. My favorite Tocqueville quote is:

“Wherever, at the head of some new undertaking, you see the government in France, or a man of rank in England, in the United States you will be sure to find an association.”

Since Election Day, I have heightened my concern that, as JFK opined, Americans are too fixated on what their country can do for them, rather than what they can do for their country. These quotes from Tocqueville seem applicable nearly two centuries after he wrote them:

"Local assemblies of citizens constitute the strength of free nations. Town-meetings are to liberty what primary schools are to science; they bring it within the people's reach, they teach men how to use and how to enjoy it."

"The greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults."

"Americans of all ages, all conditions, and all dispositions constantly form associations. They have not only commercial and manufacturing companies, in which all take part, but associations of a thousand other kinds—religious, moral, serious, futile, general or restricted, enormous or diminutive. … Nothing, in my view, deserves more attention than the intellectual and moral associations in America."

And, with great long-term foresight: "As social conditions become more equal, there is a growing tendency for people to withdraw into themselves and to take little interest in the larger society."

Interesting Happenings

I was motivated to write this piece following the end of a tumultuous election cycle in which billions of dollars were spent by each side convincing one half of the country that the other half was evil, bad, and wrong. This spending no doubt divides us politically, but my friends and colleagues have commented on the impact of a polarized political environment on their minds.

But, I was also inspired to write after watching the documentary “Join, or Die” which is available for free on Netflix right now. Borrowing the name of Benjamin Franklin’s famous political cartoon, the documentary traces Putnam’s research over many decades and shines light on the Americans who are both leaving and joining institutions — making a persuasive case that civic engagement is a prerequisite to keeping our Republic. You should watch it.

I am also incredibly excited about the launch of the “Trust for Civic Life.” I have spent hundreds of hours researching philanthropic collaboratives (plus I work for one!), and I am really excited about what Charlie Brown and his team are building. With funding from across the political spectrum the Trust is granting money to hyper-local projects to enhance civic engagement. Their first set of grantees included the Partridge Creek Farm in Michigan to expand community garden capacity, the Adirondack Foundation in New York to boost connection between citizens and provide them capacity to solve local problems, and the West Virginia Development Hub to reinvent existing local civic programs.

Finally, I am paying attention to research and programming out of the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University on the intersectionality between civic engagement, mental health, and democracy. They recently hosted a symposium on the topic.

Bottom Line

Our democratic freedoms and institutions are declining at a time when our collective mental health is taking a hit. The two are mutually reinforcing: rising polarization makes us less likely to engage across differences, and less engagement with those in our community is not good for a sense of belonging.

Unfortunately, diminished civic engagement is not just correlated with declining mental health and democratic norms but a driving force of each. When we stop spending time with each other and on solving problems in our community, we end up more lonely and more dependent on governments that are struggling to solve problems that we actually have more agency to solve ourselves.

To curb the trends, Americans must join. They must not join political movements or advocacy organizations, though they can. Participation on a soccer team, in a book club, as a member of a Kiwanis chapter, as a fan at local football tailgate, or in a farming collaborative, may not just be good for Americans’ minds, but our democracy, too.

We must Join or Die — our mental health depends on it, and so does the survival of our fragile democratic experiment.