Hello,

It’s Monday, January 29th, and this is now the seventh edition of Bipolar and Bipartisan, a newsletter designed to educate readers about a complicated mental disorder and what’s happening in the world regarding it.

Today’s newsletter gets into the three types of bipolar disorder and how researchers and medical professionals think about diagnosing individuals. When they know the difference between types of bipolar disorder, patients can get the right the right type of care while their allies can gain a deeper appreciation for what it is like to live with the disorder.

Thanks for reading.

Sincerely,

Tyler

The basics.

Bipolar Disorder is a mental disorder characterized by periods of both mania and depression.

When bipolar people are experiencing mania or hypomania, emotionally they feel “high” or “up” and can experience euphoria, happiness, extra energy, elation, racing thoughts, risky, pressured speech, and more.

When bipolar people are experiencing depression they feel “low” or “down” and can experience sadness, despair, hopelessness, fatigue, and suicidal ideation (the scariest part).

What makes bipolar a uniquely challenging disorder is that individuals can often swing from mania to depression, and back again. Sometimes this happens quickly, and other times slowly. Experience at both ends of this spectrum — the ups and the downs, the highs and the lows — is what gives bipolar its name.

The history.

Only since 1980 has Bipolar Disorder been officially listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) — the dictionary of sorts used by medical professionals to diagnose and treat mental health conditions. Of course, people experienced and exhibited symptoms much before that.

The ancient Greek physician Hippocrates, “the father of medicine,” is frequently credited as the first professional to formally document both depression and mania, around 400 B.C. It took another 2,250 years before bipolar disorder as it is currently understood today was advanced in the scientific community. In the mid nineteenth century several psychiatrists began to notice patterns in patients who experienced both mania and depression, frequently experiencing one after the other — with differing opinions on whether people lived in constant states of mood dysregulation.

Early versions of the DSM, starting in the 1950s, described both manic and depressive symptoms, along with a third category of “other,” the category in which bipolar patients were formally diagnosed. However, the illness was more commonly known as “manic depression” — a term that describes the two poles from which the eventual name would come.

The first time manic depression was separated from generalized depression in the DSM was in the third edition released in 1980, when the diagnosis was also re-named to bipolar disorder. There were many reasons for the change — primarily that the former name was stigmatized and emotionally charged. It irks me today when people say “he’s a maniac” or “that was manic,” especially in non-medical contexts.

To learn more about the history of the disorder, see WebMD, which is my source for this section.

The Three Types of Bipolar Disorder

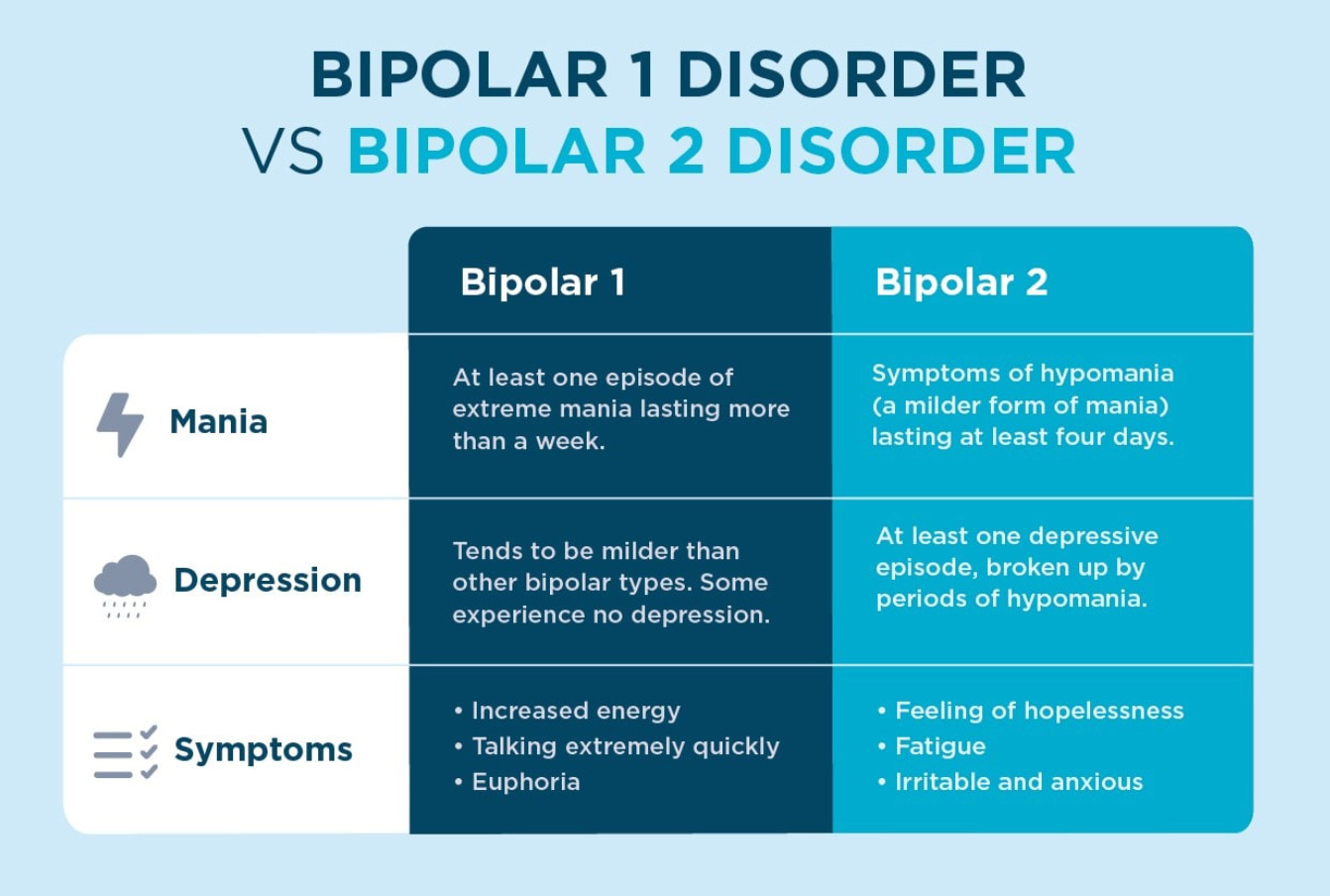

There are three types of bipolar: Bipolar I, Bipolar II, and Cyclothymic Disorder. Medical professionals also use terms like “rapid cycling” and “unspecified bipolar” for less severe cases. The major difference between the types is the severity of mania a patient experiences; depressive symptoms and severity levels can be the same among people with bipolar disorder.

1. Bipolar I is the most severe form of the disorder. To be diagnosed, patients must experience at least one episode of mania lasting for at least seven days. Depressive episodes are very common among Bipolar I patients, but they are not required for a diagnosis.

Some of the most common symptoms during episodes of mania include: an extreme increase in energy, a break from reality (i.e. psychosis), inability to sleep, paranoia, dangerous actions, heightened euphoria and grandiose beliefs, extreme irritability, and increased risky behaviors and poor judgments (e.g., excessive gambling);

People with Bipolar I are typically diagnosed following a manic episode;

Manic episodes frequently require in-patient hospitalizations, but not always. During episodes, patients are usually prescribed much stronger medications — many of which require 24/7 oversight by a medical professional.

It is very common for people with Bipolar I to fall into major depressions shortly after a manic depression. There are many potential reasons for this — ranging from disruptions to circadian rhythms, the behavioral and social consequences of manic episodes (and the reckoning that comes after them), and chemical balances — but researchers have not completely nailed down the reasons for the often rapid shifts in mood.

Personally, I am diagnosed with Bipolar I, and have twice experienced depressions that followed manic episodes. When I was first hospitalized in early 2019, I did not know I was bipolar, and being formally diagnosed was disorienting at first. It also took me a long time to find a set of medications that worked well for me, and I attribute a fair share of my nearly year-long depression that followed to not finding the right cocktail.

2. Bipolar II is experienced by more people than Bipolar I, but is still characterized by swings between feeling up and down. Using medical terminology, technically people with Bipolar II do not experience “mania” and instead experience “hypomania,” a set of behaviors less extreme than those experienced during a manic episode.

To be diagnosed with Bipolar II, one must exhibit both hypomanic and depressive symptoms. However, these symptoms can come and go, and be quite interspersed.

Because the symptoms are less severe than Bipolar I, it can take longer for patients to be diagnosed. This often leads treatment for people with Bipolar II to lag much longer following the onset of symptoms, making it harder for these patients to go through day-to-day life.

Hypomanic symptoms may include: needing less sleep, decreased appetite, more activity, pressured speech, increased sex drive, and more irritability or anxiousness than normal.

3. Cyclothymic Disorder is diagnosed among patients who experience emotional dysregulation with symptoms of both hypomania and depression, but at a severity level below those experienced by people with Bipolar I or II. People with cyclothymic disorder can explicitly notify when moods shift up and down.

This disorder is rarely diagnosed, but does disrupt the daily lives of people with it.

Importantly, people with cyclothymic disorder still need treatment. Like with other types of bipolar disorder, mood stabilizing medication, therapy, and other strategies and skills can make living with this disorder easier.

Priory’s simple chart helps distinguish the two most common forms of bipolar disorder.

Other Terms.

There are other terms used by medical professionals working with bipolar patients, too.

“Rapid Cycling” designates patients who have experienced at least four episodes of mania or depression in a single year;

“Unspecified Bipolar Disorder” is used to describe the presence of bipolar like symptoms for patients who experience mood swings at a severity level below cyclothymic disorder;

“Co-occuring conditions” refers to other mental health diagnoses bipolar patients have; people with bipolar are frequently diagnosed with anxiety, ADHD, substance abuse disorders, and psychosis;

People with bipolar disorder are also often misdiagnosed at first, with men more likely to be misdiagnosed with schizophrenia and women with depression;

“Mixed Episodes or Mixed States” refers to when people experience mania or hypomania and depressive symptoms at the same time;

“Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Disorder” acknowledges that some bipolar patients — perhaps up to 25% — see very few or no interventions work with clear effectiveness;

“Atypical bipolar” refers to symptoms that show up during episodes that run against common patterns — like hypersomnia, weight gain, or increased appetite during periods of mania.

Bipolar Disorder as a Spectrum.

In the 1980s, some doctors proposed designating cyclothymic disorder as Bipolar III and adding Bipolar IV (when manic or hypomanic symptoms only arise after taking antidepressants) or Bipolar V (when patients have family history of bipolar disorder, but only experience depressive symptoms).

As research on bipolar disorder has advanced and medical professionals have better documented the common symptoms and their varying degrees, bipolar disorder has increasingly been seen as a spectrum. Researchers are still trying to parse this out, and there is not unified consensus.

Personally, I’m quite sympathetic to the proposition that bipolar disorder occurs at a wide range of severity levels. Suggesting that all bipolar patients — of which there are 6.3 million in the United States alone — into just three categories of severity is likely insufficient to capture the diversity symptom severities experienced. Yet, the DSM's current framework, which categorizes bipolar disorder into three common forms, helps medical professionals provide the appropriate level of care, particularly in terms of medication, to patients — which is of utmost importance.