My take on the macro mental health puzzle

How I think about the challenges facing the mental health system and advocacy community in America.

Hello,

It’s Saturday, March 22nd and this is Bipolar and Bipartisan, a publication designed to educate readers about a complicated mental disorder and what’s happening in the world regarding it.

My writing today is a foundational piece, on which I hope to build upon in the future. I have been diagnosed with bipolar disorder for six years, and I have been thinking a lot about the macro picture on how America approaches mental health for some time now. Over the last few months, the intensity of my research and reading has picked up. Today’s post introduces the big picture puzzle I have been wrestling with, and some potential ways to solve that puzzle.

As I have gone down rabbit holes on mental healthcare and public policy, I keep coming back to three facts:

We know more about mental health than ever.

Mental health is more destigmatized than ever.

And yet we are worse than ever.

These are non-negotiable facts. While we may be making progress in some leading indicators of individual or collective mental health, there is no refuting that on trailing indicators we are still going in the wrong direction. Suicide rates are higher than ever; depression diagnoses are going up; substance abuse deaths are more common; reports of loneliness are through the roof. And, so much more.

How could that be? Below I offer at least twelve potential explanations. They are, succinctly:

The criminalization of mental health;

Increasing access to hard drugs;

Toxic social media and addictive phone technology;

Declining free play in childhood;

Declining civic engagement;

Declining marriage rates;

Declining bed capacity for in-patient psychiatric care;

Declining number of providers in mental health workforce;

Rising reliance on medication in treatment;

Lack of economic mobility;

Millions of Americans do not seek care;

Bad public policy.

I am curious for reader feedback. What resonates? What else should be on the list?

Thanks for reading. This may be the longest post I will ever write on this platform, but it is the most important. If you do nothing else, check out the charts below. A picture is worth a thousand words.

Sincerely,

Tyler

The situation.

We know more about mental health than ever.

Perhaps this is obvious. Our individual and collective understanding of the world is driven by scientific discoveries, discoveries that build on previous ones. It is hard to imagine knowing less about mental health than we did before.

Nevertheless, the last few years have seen an explosion of new research and understanding of mental illness. This is in part due to the Covid pandemic, but not only because of it. A 2024 bibliometric analysis by five scholars quantitatively analyzed 7,047 publications from 110 countries on the topic of mental health. In 2021, there were more than double the number of publications on the topic as there were in 2020. By 2022, the volume of mental health publications had tripled since 2020.

The accumulation of knowledge is no small part due to the contributions of many generous philanthropists and advocacy of elected officials. Since 2017, the National Institute of Mental Health Budget has increased from $1.48B to $2.32B.

Research is not only funded by governments, though: Over the last 25 years, OneMind has raised and spent $546M on brain health research. Meanwhile, the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (BBRF) has invested $462M on more than 6,700 research grants since 1987. New efforts are addressing diagnosis-specific questions, too. For example, Breakthrough Discoveries for thriving with Bipolar Disorder (BD2) was started in 2022 with a $150M commitment from three families to better understand and treat the disorder I, and 40 million others globally, are diagnosed with.

Talking about mental health is more destigmatized than ever.

This may also be obvious, but not every person may experience this reality.

Because of the brave and courageous actions of people with mental illness happening every single day, conversations about mental health are more frequent and more normalized. To be clear, we are far from where we need to be, but we are headed in the right direction. Americans self report destigmatization. In 2021, 56% of Americans agreed there was less stigma towards people with mental illness than there was in 2011; only 15% disagreed.

These results are similar to a study published in 2021 by Bernice Pescosolido, Andrew Halpern-Manners, and Liying Luo who reported on surveys of Americans over a 22 year period from 1996 to 2018. In the early years, attitudes towards people with schizophrenia, depression, or alcohol addiction did not change significantly. But, from 2006 to 2018 the number of people saying they desired social distance from people with depression in the workspace decreased by 18%, as well as for socializing (16.7%), friendship (9.7%), family marriage (14.3%), and living in a group home (10.4%). The authors credit a generational shift in attitudes about mental health:

Destigmatization is not just an end in itself. Peer support — when someone with mental illness gets help from a community member — has a strong evidence base in improving brain health outcomes. An innovative recent study examined 2 million Twitter/X posts by 10,000 users and found “engaging with coping stories leads to decreased stress and depression, and improved expressive writing, diversity, and interactivity.” A World Psychiatry study split 1,023 people in England into two samples and gave one group easy access to 600 recorded online narratives about mental health recovery. The group that received access to the stories reported significantly better mental health outcomes one year later, compared to the control group. These benefits were one third the cost to the National Institute of Health (NIH), compared to the cost of other interventions capable of delivering the same benefits.

And yet we are worse than ever.

That sentence is hard to write. As a person living with mental illness, the macro, societal environment I am living in makes it more likely than in years past that I will be depressed and lonely; and, of course, more likely to commit suicide. That environment is the same environment everyone with severe mental illness, and indeed all of humanity, is living with.

Suicide rates are perhaps the most clear and quantifiable indicator that tell us how we are performing on mental health. The data are not good. According to the CDC, suicide rates increased by 36% from 2000 to 2018 before seeing a brief decline and then another increase. This represents an increase from an average of 10.4 suicides per year per 100,000 Americans to 14.2.

Suicide is disproportionately impacting men, who are four times more likely than women to take their own life. The challenges facing men in society are many, and are well explained by the book “Of Boys and Men” and the organization American Institute for Boys and Men.

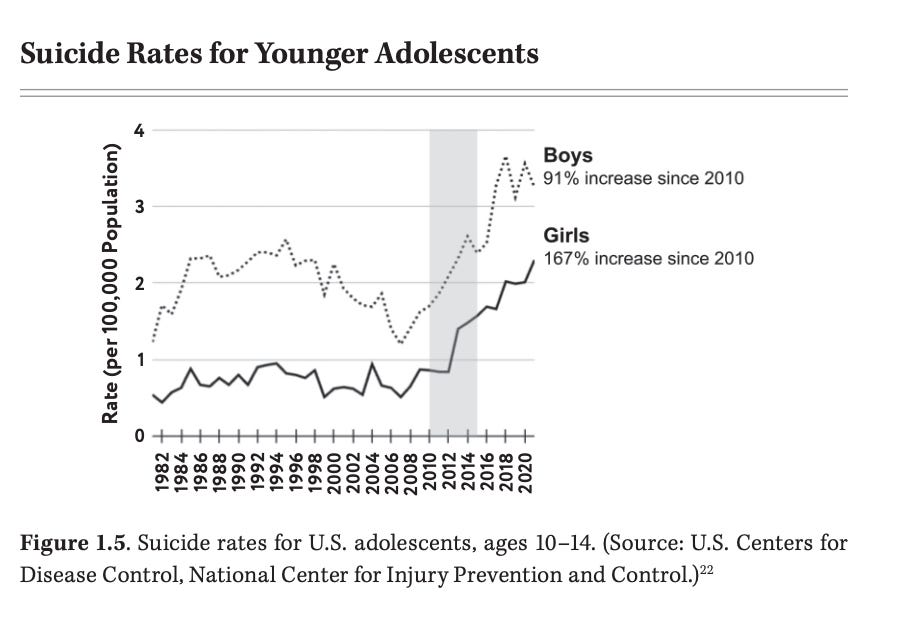

While suicides disproportionately impact men, the largest driver of the increase in suicide rates are the increases in teen suicides. Since 2010, there has been a 91% increase in adolescent boy suicides and a 167% increase in girl suicides.

These data are extremely sad. Unfortunately, they are not the only ones. A meta analysis of 345 studies from 1967 and 2019 found that loneliness has steadily been on the rise. A 2024 survey by the American Psychiatric Association found that 30% of adults report feeling lonely at least once per week for over a year, with a staggering 10% reporting feeling lonely every day. Alarmingly, among Americans 18-34, 30% said they were lonely every day. All of these numbers are up significantly from previous decades, and it is only a recent phenomenon that young Americans are lonelier than older Americans.

Depression and anxiety rates are climbing, too. Reports of one depression in a lifetime have increased by 50% in just the last decade. Increases are highest among women, young adults, black, and hispanic adults. In 2024, 43% of Americans said they experienced higher anxiety rates than in previous years. Importantly, some of the increased in reported rates of anxiety and depression can be attributable to stigmatization progress that makes people more comfortable reporting their illnesses — but the increases cannot fully be explained by this factor.

If that is not enough to dread, let’s return to death. “Deaths of despair” refer not only to suicides but also to those caused by substance abuse — including of alcohol and other hard drug. The data here are particularly bad. Over the past 20 years, drug overdose deaths in America have tripled. Men and Americans aged 35-44 have been hit hardest.

Make no mistake: there are many positive signs that our country and world are moving forward on mental health. There are many data that suggest we may be curbing the tide and making progress. But that progress is mostly on leading indicators, not the trailing indicators that actually matter the most. To recall a high school physics experiment, we still have velocity going in the wrong direction, but we may no longer be accelerating. Yet, the truth remains Americans are more lonely, depressed, anxious than ever before — and the saddest result is that suicide rates are still going up.

How Could that Possibly Be?

There are many reasons we are worse than ever on mental health outcomes. I am certainly not an expert, but as I have read about this issue over the last many years I have started to form some thematic hypotheses. The sections below offer some explanations with a few data points and an infographic. I hope to explore some of these themes over the coming years in more detail.

Explanation #1: The Criminalization of Mental Health

If a person with severe mental health is going through a psychotic event or other crisis there is a 25% chance they will be homeless, a 25% chance they will be receiving care in a healthcare setting and a 50% chance they will be in a jail (Tom Insell in Healing). The three largest providers of psychiatric care in America are jails: Rikers Island in New York City, the Twin Towers in Los Angeles; and Cook County Jail in Chicago. 2 million Americans with mental illness each year are put in jails, and 40% of inmates have a mental illness. It was not always this way: In 1930, someone with mental illness was about two times more likely to be in a hospital than a prison, but today they are at least six times more likely to be in a prison. This problem is the subject of an entire book: Insane: America's Criminal Treatment of Mental Illness.

The consequences of these data are unspeakable. Often, people in prison cannot even stand for trial because they lack “competency.” Prisoners often spend 23 hours per day in solitary confinement, which only makes mental illness worse. We are barely doing better than parts of the world known for shackling people with mental illness. Prison staff are wholly under-resourced and not trained on how to provide mental healthcare. Families — often the most important people who help patients recover from and cope with mental illness — cannot be near their loved ones. The financial costs to taxpayers are staggering.

Explanation #2: The Rise of Substance Abuse

More than 5 million Americans struggle with opioid use disorder, and 75% lack access to FDA approved treatments. Approximately 125 million opioid prescriptions were authorized in 2023. Because it has become more accessible while becoming cheaper, heroin abuse has skyrocketed. Over just a six year period from 2010 to 2016, deaths from heroin use increased by 510%. 28.9 million Americans have alcohol use disorder, including more than 750,000 kids between the ages of 12 and 17.

The rise of pharmaceutical prescriptions from licensed healthcare professionals led to a huge spike in hard-drug use and deaths of despair. Companies, providers, and patients all have responsibility. An insecure southern border has compounded this problem. In December 2024, 1,100 pounds of fentanyl were seized at US borders (that is just one drug in one month!).

People with substance abuse disorders often experience more stigma from their social networks — and public policy has generally failed to treat substance abuse the same as other mental health disorders. All of that despite rigorous research that shows abuse of drugs has genetic and hereditary predispositions that definitely show these disorders often arise from defects in the brain — just one of many organs in our body that our healthcare system should treat.

Explanation #3: The Rise of Social Media and Addictive Phone Technology

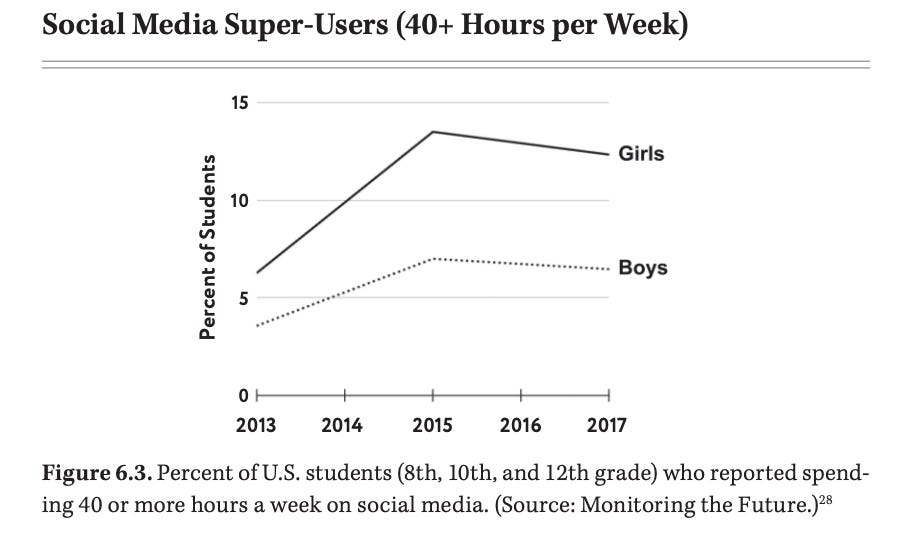

A frequent culprit, the digital environment Americans — and especially children — experience has made mental health outcomes worse. Jonthan Haidt’s recent tome on this topic, Anxious Generation, is a must read — but he has also published all of his charts in one place. Globally, people spend over two hours a day on social media. Over 10% of teenage girls spend at least 40 hours per week on social media (nearly seven hours per day!). The average teen spends 4.8 hours per day on social media. Adults spend an average of 4 hours and 37 minutes per day on their phone, the equivalent of six days per month.

As we all have increased time on our phones, we have decreased the time we spend with friends and family — tanking senses of belonging. The light on our phones is terrible for sleep, which is very important for mental health. Not just that, but the way that our phones and social media platforms work actually rewires our brain in ways that both necessitate more medication while making medication less effective. When teenage girls, especially, spend time scrolling their sense of self deteriorates. When teenage boys, especially, spend more time on the internet they are spending more time watching porn — a trend that has been correlated with the decline in sex, an activity many studies have found drives life satisfaction.

Explanation #4: The Decline of Free Play among Children

“Helicopter” parenting may be too strong of a word, but the data is clear that children spend less time playing than ever before. According to data summarized by Haidt, the percentage of students who meet up with friends daily has been cut in half since 1991. Compared to 1970, children spend 50% less time on unstructured outdoor activities. First graders in low income schools are five times more likely to have no recess time, compared to the same students in wealthier neighborhoods. All this despite the fact that 80% of parents say unstructured play is very or extremely important and overwhelming data that free play reduces anxiety and depression later in life.

The trends are, in part, the result of; the sensationalizing of a few high profile cases of childhood abduction by traditional and non-traditional media — despite the fact that child abductions are rare and becoming less prevalent (in just seven years from 2015 to 2022, the number of involuntary missing children declined by 27%, according to the FBI).

Free play is important for all sorts of reasons. Exercise and sunlight exposure is very good for the brain. Free play teaches children to resolve differences among themselves, keep themselves and their peers safe, and form new friendships and relationships. Unstructured play also empowers children to explore, gain self confidence, and develop resilience. Children roaming free is also very important for parents: it gives them more time to engage in self-care and socialize with their friends and families; it also makes parents less anxious when their children eventually move out of the home.

Explanation #5: Decreased civic engagement.

As time on our phones and watching television has rapidly decreased, time spent in our communities has plummeted. This was the subject of a recent Atlantic essay “The Anti-Social Century” and one of my publications “Democracy and Mental Health are Linked.”

Belonging to unions has been cut in half since 1983 and to religious institutions by a third since 2000. Fraternal memberships — much more broadly defined than Greek “frats” on college campuses — are way down. Groups like the Elks Club, the Odd Fellows, and the Free Masons have declining memberships (in 1951 a staggering 4.5% of American men were Free Masons, down to 1.1% today). Charitable giving is down, as is attendance at local government meetings. Volunteering has hit 50% since 2005.

Civic engagement matters for our minds. When you spend time with others, you are much less likely to feel lonely. Less loneliness makes it less likely you will abuse substances, commit suicide, or experience anxiety and depression. It is not just that spending time outside the home connects you to others, it helps people find a sense of purpose in life. A sense that you are contributing to a stronger and healthier society is really healthy for your brain. Plus, engaging with others in community can help solve local problems and contribute to a richer and more pluralist democracy.

By the way, this is crazy. Among people who report feeling lonely every day, 50% report easing their loneliness by watching television or being on their phone while only 38% say they address it by spending time with friends!

Explanation #6: Declining marriage rates

One of the most significant predictors of happiness is marriage. A 2024 study on American happiness found that being married was the most significant factor in a person’s happiness. Married men benefit most: they are about twice as happy once they are hitched. Short of marriage, co-habitation leads to happiness boosts, equivalent to about 2/3rds the benefits of marriage (at least, for Germans). Despite all the benefits of marriage (which go way beyond happiness) marriage rates are way down.

Want to feel better? Get married! I was in a deep depression when I met my now wife. While there were a number of things that changed around that time, I credit our relationship as the most important factor that made me feel less blue. Of course, marriage is easier said than done. But, it is no accident that Americans’ choices to spend less time on civic engagement and more time on their phones has been correlated with declining marriage rates.

Explanation #7: Reduced bed capacity for in-patient psychiatric care

One of the most sad stories in U.S. Mental Health public policy is the half-filled promise of President John F. Kennedy Jr.’s Community Mental Health Act. Motivated by his sister’s heartbreaking and tragic experience in America’s mental health system that included lobotomy, JFK’s 1963 law was to change everything. In the only ever special message to Congress about mental health, he proclaimed:

“[R]eliance on the cold mercy of custodial isolation will be supplanted by the open

warmth of community concern and capability. Emphasis on prevention, treatment and

rehabilitation will be substituted for a desultory interest in confining patients in an

institution to wither away.”

In short, the bill aimed to do two things. First, defund and discourage large asylums, mostly run by state governments, wherein mentally ill patients were boarded together with little healthcare and minimal dignity. Second, motivate, empower, and support communities in delivering quality mental health care. We did the first part. We never did the second part. Though attempts were made and there have been success stories, the decentralization of the provision of mental health care has resulted in a patchwork of service providers. No one is in charge, and no one is accountable for results.

One of the most tangible and quantifiable consequences is the decline in mental health beds for patients with high acuity needs. During the major years of deinstitutionalization — from 1970 to 1983 — Americans lost 52.3% of our psychiatric bed capacity. No doubt this period of time was marked by many people with mental illnesses receiving much more dignified and professional care. Yet, the lack of beds in community based healthcare centers has made our current crisis nearly impossible to control.

While the nosedive is behind us, the problem of declining bed capacity continues today. Half of the number of in-patient healthcare facilitates available to children experiencing a mental health episode in 2010 have closed; this time period has seen teenage suicide rates sky-rocketed. Just this week, the Colorado Sun reported that 500 mental health workers at three now closed psychiatric hospitals have been laid off since December. This only adds fuel to the fire in my home state: we already have the third longest wait list for psychiatric beds.

There are countless reasons why we are losing bed capacity, among them that providing psychiatric care is very expensive and the ability of facilities to be reimbursed for the full costs of stays by governments for people without insurance is diminishing. The rise of substance abuse disorders that require in-patient stays has created new demand, and many facilities that used to primarily serve people with severe mental illness have become facilities to treat substance abuse.

Importantly, as bed capacity decreases, incentives change. Psychiatric hospitals are pressured by governments and financially incentivized by markets to quickly make room for the next group of patients — often leading doctors to prescribe very powerful medications that are not safe in out-patient settings. In short, psychiatrists running mental health floors do everything they can to get patients to calm down as soon as possible by providing patients immediate relief. Patients then leave hospitals to make room for the next crop of patients waiting in jails or emergency rooms. But, because they have not been steadily taking medications that work for long-term maintenance, patients often end up back in the same hospitals days, weeks, or months later.

Twice I have been hospitalized at in-patient hospitals. This was a horrible pattern in both facilities. Most of my peer patients had been to the same facility countless times. Of those, most understood the fastest way to escape bad treatment was to take powerful drugs they knew would not be the ones they would want to take when they left.

Explanation #8: A shrinking mental health workforce

If the seven explanations above are even remotely directionally correct, it is no wonder that we have a mental health workforce that is burnt out. As workloads increased during Covid, mental health workers reported a noticeable difference in their own mental health. In 2022, the American Psychological Association found that 38% of psychologists were working more; 45% reported feeling burnt out; and 46% said they could not meet the demands of their patients.

Supply of providers is not keeping up with demand. That same year, The Kaiser Family Foundation found that 47% of Americans were living in areas with a mental health workforce shortage. More than 700 workers needed to be hired in several states just to meet current demand.

Quite intuitively, when providers work longer and more stressful hours, their mental health begins to take a hit. In 2023, the CDC found that 53% of healthcare workers reported feelings of anxiety and 31% reported feeling depressed. Those numbers rose to 85% and 61%, respectively, if the worker had been harassed at work.

One sad consequence of the often horrible way in-patient facilities are run is that providers and patients get pitted against each other. Last year, I testified in the Colorado legislature about why I thought it was important to be cautious in criminalizing the behavior of often aggressive patients during in-patient stays: if our hospital systems deny us the right to speak with a lawyer, barely allow us to speak with a psychiatrist, limit the amount of time we can spend with family, and deny us our rights, it seems wrong to penalize patients under the law. But, on the other side of the debate were mental health nurses telling horrifying stories of being peed on, verbally abused, and physically assaulted. It is unfortunately common for mental health providers to die in the line of duty. From 2011 to 2018, about 20 healthcare providers died per year while on the job, with about one sixth attribute to patients committing murder.

Explanation #9: Overreliance on medication in treatment

Brain health is a complicated field. Serious mental illness and other diagnoses are often the result of irregular brain activity. The brain is an organ, and there are many ways to treat that organ. For the most part, however, mental illnesses are chronic, meaning they cannot be cured. As a result, most medications are designed to mitigate symptoms. And, those medications can have horrible side-effects.

For example, Seroquel – the drug I take to treat my bipolar diagnoses — has a major sedating impact and is correlated with weight gain. I take Seroquel because Lithium – the most common drug to treat bipolar disorder — is associated with nausea, blackouts, and bad eyesight; long term, being on lithium can have devastating impacts on your kidneys and thyroid. These side effects often discourage people with severe mental illness from taking medications and in one of the most troubling realities of mental health care, people stop taking medication once they start to feel better because they cannot tolerate the side effects of their drugs.

There are two primary upstream solutions. First, we need more medical innovation. Unfortunately, today, most pharmaceutical companies are trying to mitigate the side effects associated with existing drugs, not trying to actually innovate in how effective the medications are in mitigating symptoms. Second, we must center other forms of mental healthcare in how we approach our disorders. Both will help us re-calibrate medication as just one of many ways to treat mental illness.

Medication management is only one of the top six ways I manage bipolar disorder. I often tell people, for me, it is about: sleep, diet, exercise, emotional regulation, emergency preparedness, and medication management. There are many other evidence-based treatments for mental health diagnoses, ranging from therapy, peer-to-peer support groups, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), and meditation. Even lower cost and lower barrier interventions like journaling, getting more sunlight, and getting at least eight hours of sleep each night can make a difference.

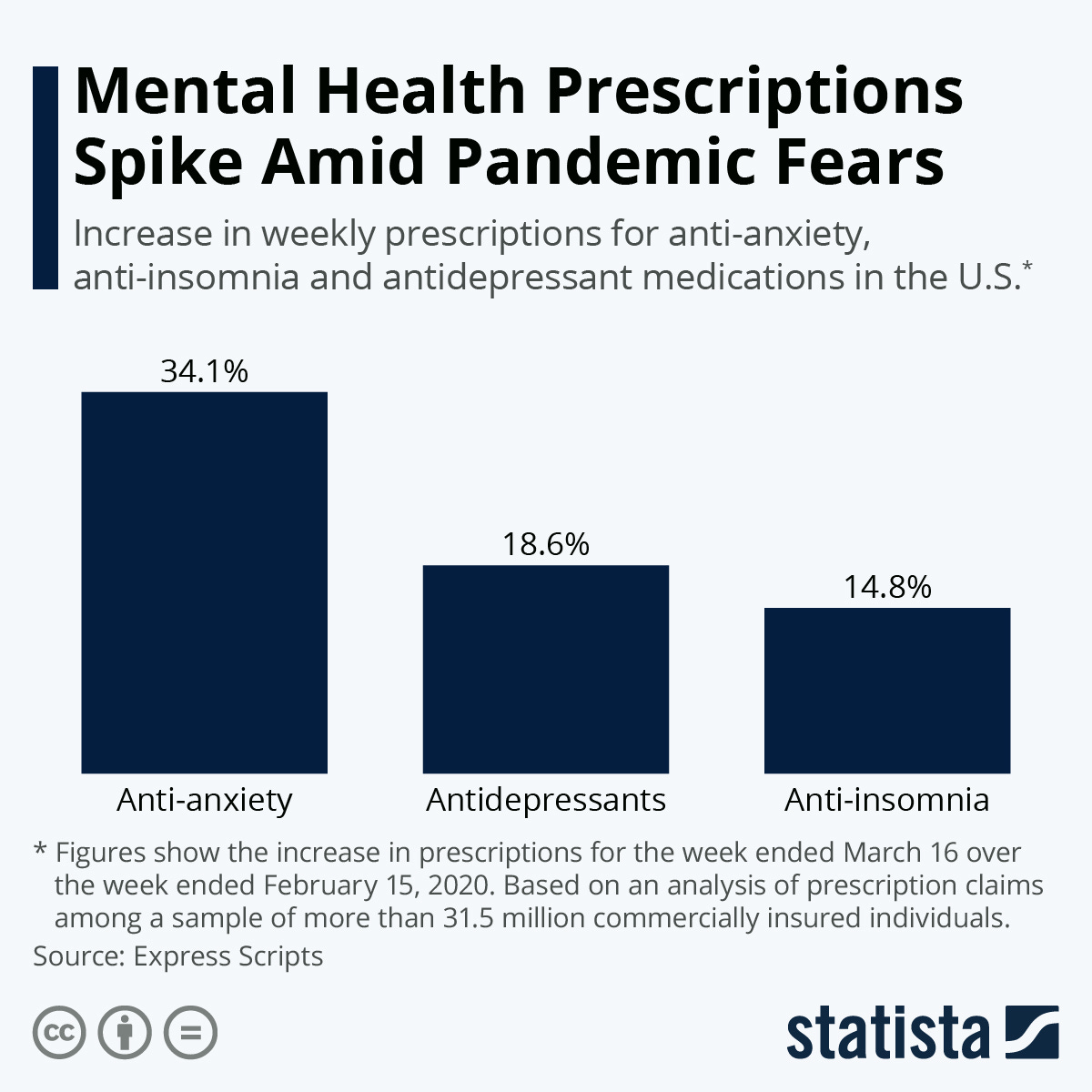

I worry that the current uptick in medication prescriptions is not just being driven by an increase in mental health diagnosis, but rather a trend to make medication the first (and only) hammer to do the job. By May 2020 — just three months after the onset of the Covid pandemic — anti-anxiety prescriptions were up 34%, antidepressants up 19%, and anti-insomnia up 15%. The early days of the pandemic offered most people (with significant exceptions) more time to cook at home, exercise, sleep longer, do meditation, and more. Yet, prescriptions became a key remedy for a lot of people, fast.

Make no mistake, taking medication is often the right thing to do. I take 13 pills per day. I take two drugs to manage my bipolar (Seroquel and Lamichtal), one drug (Metformin) to manage weight gain side effects, and two vitamins that research finds help people with bipolar disorder (Vitamin D and Fish Oil).

Explanation #10: Lack of economic mobility;

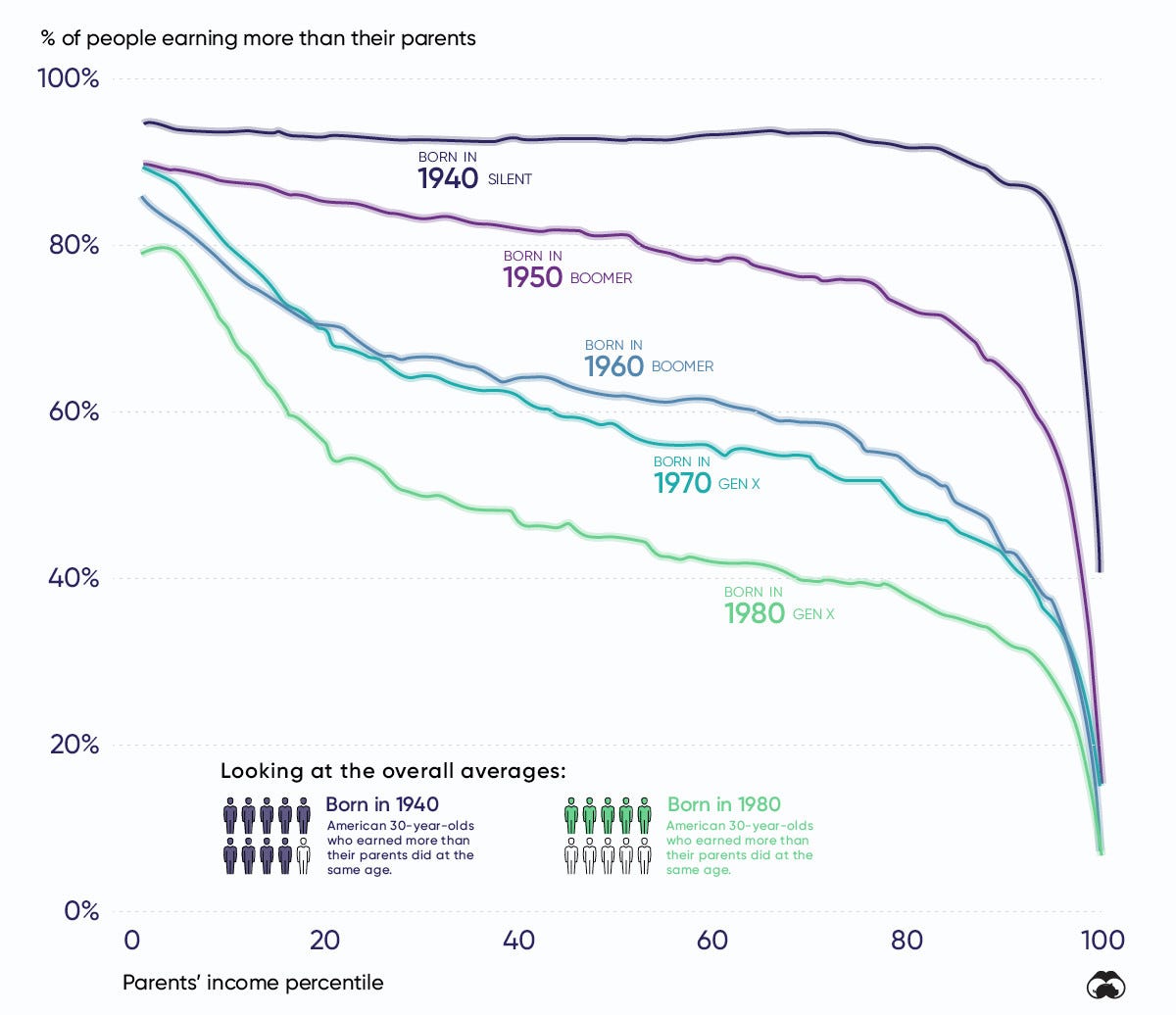

There are many socio-determinants of health. Race, gender, physical environment, early childhood experiences, education level, and more have been shown by researchers to impact quality of health in individuals. Personally, I believe the lack of economic mobility explains some of the mental health crisis. The number of Americans that make more than their parents in inflation adjusted dollars is plummeting. 43% of American families fall short of meeting basic needs: black (59%) and hispanic (66%) families come up short more often. While overall wealth is increasing, inequality is, too. These factors and more contribute to a lack of economic mobility: those who start in the bottom quintile of wealth have a 61% chance of staying there, but only a 6% chance of reaching the top one.

This is important for many reasons. Perhaps most obviously, macro economic success puts more money in the pockets of Americans, and those dollars can be used to pay for mental health care. Economic outcomes are highly correlated with homelessness rates, and homelessness intersects with mental health outcomes considerably. But, the lack of economic mobility matters for psychological reasons, too. For many Americans, the American dream — the idea that anyone can work hard and make a great life — is not a reality. The ability to be a breadwinner for your family, earn more than previous generations, and find purpose in life through impactful work all matter to one’s mental health. `

Explanation #11: Millions of Americans do not seek care

There are about 15 million American adults living with Severe Mental Illness (SMI). SMIs include schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder, post traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, and major depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, and panic disorder. Of these individuals, only 67% received any type of care in 2022, according to the National Institute of Health. Other researchers say the number is lower. This is startling and very problematic. This means there are about 5 million American adults with a severe mental illness that are not being treated with psychiatry, therapy, EMDR, or any other common form of mental health treatment!

This is not just true of people with Severe Mental Illness. Of those with Any Mental Illness (AMI), just 50.6% received care in 2022. That leaves 29 million Americans with a mental health disorder who are not receiving care.

There are many reasons people do not get care. Lack of health insurance is a part of the story, but — in my view — not the most important factor. The extremely poor mental health system in the United States, from the way we criminalize care, stigmatize illnesses, put medications with strong side effects at the center of care, to the lack of mental health hospitals and workforce all discourage people from seeking care. Boosting the number of Americans who seek care would make a major difference in mental health outcomes.

Explanation #12: Bad public policy

All of the above explanations can be explained, in part, due to public policy. Public policy is not the only nor the most important culprit, but the ways in which our country’s laws and regulations regarding mental health shape our system are far from ideal. After federally directed de-institutionalization in the 1960s, states and localities never picked up the responsibility of delivering community based care. Federal and state laws do not require health insurance companies to cover brain health like they cover treatment for other organs in the body (something that will change after a law passed this week!).

Colorado joins only nine states that had similar protections earlier in the year. Only 24 states have laws governing how insurers conduct behavioral health reviews. There are 19 states that do not require health insurers to disclose what mental health benefits they offer when plans are being sold.

In many states, you can be sent to jail during a psychiatric episode, even if you have not committed a crime! This form of “civil commitment” is the most unjust, but laws mandating holds at in-patient psychiatric hospitals do not always guarantee patients basic human rights. Local governments could save themselves millions of dollars by investing in more preventative interventions to avoid expensive emergency room bills. And, so much more.

Public policy matters a lot. At its best it can solve systems-wide problems driving our mental health system to the brink. At its worst, it can exacerbate challenges and contribute to poorer outcomes.

Yet, the promise of public policy is what makes me most optimistic about the future of mental health care in America. Unlike nearly all other issues facing our local, state, and federal lawmakers, mental health is not clearly partisan. State elected officials are introducing and passing bipartisan laws every day. States are realizing they need to establish agencies explicitly focused on mental health outcomes — many of which are charged with the critical work of implementing good laws when they face.

As an antidote to national politics, Congress is taking action on mental health. There are bipartisan caucuses in both the US House and US Senate agreeing to comprehensive agendas. Last year, in one of the most encouraging developments for mental health, the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA) passed the US Senate with 91 votes. Unfortunately, it was not included in the reconciliation package that passed at the end of 2024 (bills getting their own votes in Congress is less and less common, a major problem).

The Bottom Line

Our mental health outcomes are worsening. The data are definitive on that point. And, it is a system — which means there are an untold number of factors that impact both individual and collective outcomes. The above dozen explanations are just some, which I’ve summarized based on my interactions with some of the incredibly smart advocates doing this work every day and the researchers who have given the world rich data to understand these problems.

Importantly, these issues intersect with each other. As mental health bed capacity has diminished, police officers have increasingly brought people disturbing the peace due to a psychiatric event to jails. As we engage less with our community, we are less likely to meet a spouse. Because phones have addictive capabilities, children are participating in less free play. The rise of substance abuse disorders, which is more prevalent in lower income brackets, has impacted economic mobility.

There is one important item not on my list that would be on many others’: health insurance and health insurance companies. Something that is getting better cannot explain something that is getting worse. More Americans have health insurance than ever. Increasingly, mental health coverage is included more comprehensively in mental healthcare plans. Neither fact is where we need to be, but things are getting better in this domain.

No doubt, health insurance companies have profit motives that have – at times – got in the way of delivering quality mental healthcare at low costs. But the villainization of them by many advocates and onlookers does not resonate with me. The data on how those companies have driven the crisis is not clear to me. Perhaps I am wrong, and I am more than eager to be persuaded otherwise.

The problems are many. The solutions are vast. This post has not covered solutions. At the end of the day, I am an optimist. I am an optimist because the issue remains largely nonpartisan, because there are courageous and talented people working to fix the system, because everyday Americans are speaking up and destigmatizing the topic, and because researchers are innovating in treatment methods.